johndoe@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

To celebrate the 2025 International Medieval Congress at the University of Leeds, UK, we have brought together some key resources on the special thematic strand, ‘World of Learning’.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies is dedicated to opening up the medieval world for scholars, instructors and researchers of this fascinating field of study, offering a carefully curated collection of just a few of the valuable resources from across the platform designed to support teaching and learning. From digitized primary sources, an exclusive global Encyclopedia, and secondary analysis, to specially commissioned teaching and learning tools, and exclusive audio recordings of Medieval literature, let Bloomsbury Medieval Studies enhance your studies.

Enrich your course building or expand your own research with the dedicated teaching and learning resources gathered together here.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides access to a range of pedagogical teaching and learning tools, all written by expert scholars exclusively for the platform. The resources are designed to introduce students to key subject areas, support instructors to bolster their courses, and serve as jumping-off points for further research. The Lesson Plans help to support teaching and individual learning with links to additional reading, discussion topics, and homework assignments across a range of key topics, such as women and gender, medicine, the Islamic golden age, the Byzantine Empire, the Medieval Mediterranean and much more. The plans can also be used as navigational tools to assist users make the most of the variety of content available on the site.

➜ Read the full list of Lesson Plans now.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies offers an exclusive series of Introductory Articles covering key subject areas within Medieval Studies from a global perspective to support students new to the field, and provide instructors with useful resources that they can utilize to globalize and expand their curriculum. Each article offers a comparative overview of important topics, outlining the key events, figures, scholarship, and areas of debate, alongside a thorough bibliography of key reading to support further studies. Topics include race in the European Middle Ages, African Kingdoms, the Crusades, Medieval music, medieval climate and environmental histories, the Knights Templar, Old Norse-Icelandic palaeography, and more.

➜ Learn more about the Medieval world.

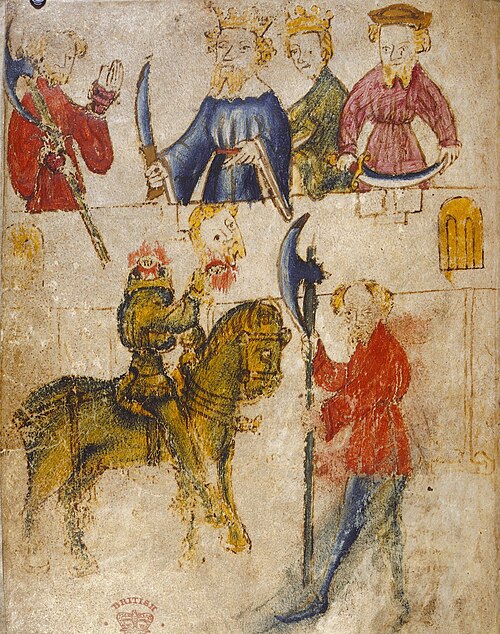

Written and peer-reviewed by expert scholars in their field, this growing series of primary source commentary articles is designed to bridge the gap between primary and secondary content, and introduce students to the digitized manuscripts, maps and incunabula available on the platform. Each article accompanies one of the medieval primary sources, providing a historical commentary with a description and analysis of the source as an object and an exploration of the different disciplinary approaches through which it can be studied. Works include The Malleus Maleficarum, The Ramsey Abbey Map, The Vision of Piers Plowman, Francesco Petrarca’s Trionfi E Canzoniere, and many more key Medieval texts.

➜ Discover more now.

Explore high-resolution digitisations of works from some of the most important Medieval writers, from Chaucer and Petrarch, to Langland and Boethius. Covering themes of magic, astronomy, philosophy and more, these illustrated manuscripts and incunabula enable students and instructors to discover each page in exquisite detail and draw informed conclusions about the text. These invaluable texts sit alongside a collection of digitised 12th-15th century maps from the British Library. The digitized editions of works by Matthew Paris, Ranulf Higden, Bartholomaeus Anglicus and more, allow users to explore how contemporary cartographers understood the Medieval world.

➜ Explore the full collection of Maps and Manuscripts.

Medieval Literature Aloud: Chaucer Studio Audio Collection is an unrivalled learning resource for scholars and students of Medieval literature that provides exclusive access to audio recordings of key works read aloud by leading experts, alongside a curated selection of scholarly eBooks. From Beowulf and The Canterbury Tales, to Le Morte d’Arthur and Piers Plowman, this unique collection includes full recordings of the most commonly studied core texts on Medieval literature and language courses making it an invaluable resource to support users seeking to hone their pronunciation, and enhance their understanding of the original cultural contexts within which these vital works of literature would have been performed and experienced.

➜ Explore the full list of recordings.

Since it was founded in 1870, The Met’s treasury of rare and beautiful objects has provided a means of understanding art and objects across times and cultures. Over 1000 select images from the Met’s collection have been included in Bloomsbury Medieval Studies, providing context for Medieval History across the globe. With content ranging from 4th to the 15th century, the Met image collection compliments academic research and allows for a more well-rounded and inclusive understanding of medieval history. From chalices and tunics, to scrolls and swords, the carefully chosen Met images illustrate the life and history of the Medieval world.

➜ Explore these fascinating objects.

The Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages is an exclusive reference work commissioned for the Bloomsbury Medieval Studies platform. It takes an inclusive approach to the history of the middle ages. It includes overviews based on specific regional areas as well as thematic overviews of key concepts within their global contexts, while Case study articles provide deep dives into how these broader themes can be explored through specific, global examples. The encyclopedia aims to provide readers with scholarly articles by global contributors and specialists in all things Medieval, to bring the Medieval world alive and present how, as today, diversity and connection competed with isolation and conflict during this significant era in global history.

➜ Click here to discover the full article list.

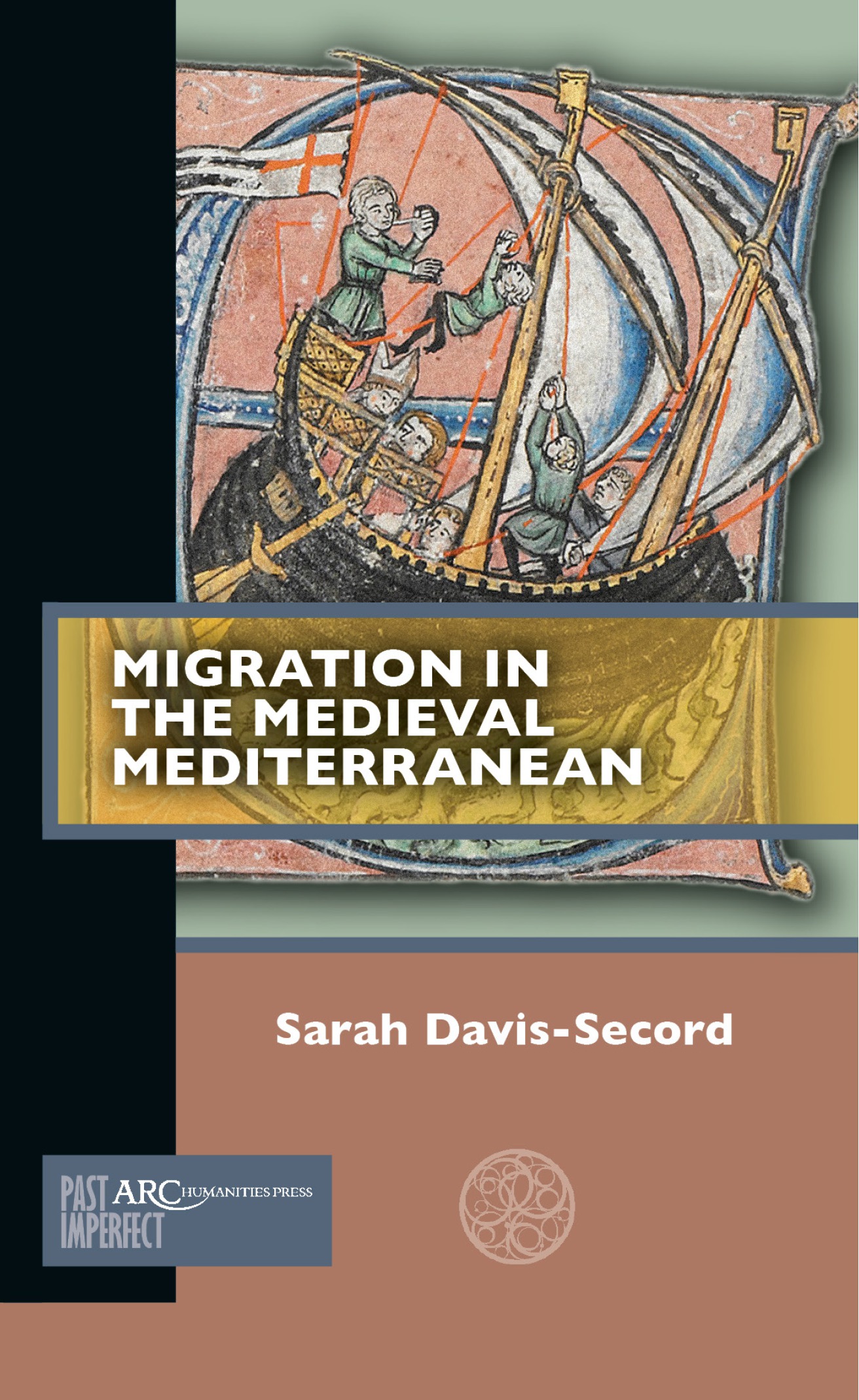

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies features hundreds of eBooks hand chosen by our Editorial Advisory Board, including scholarly monographs, companions and primary texts from Bloomsbury and a range of top publishers in the field of Medieval Studies, including IB Tauris, ABC-Clio, Arc Humanities Press (including the ‘Past Imperfect’ series) and Amsterdam University Press. These books are fully indexed and cross searchable by keyword using our custom taxonomy. The collection brings the global middle ages to life and enhances academic research with a unique, interdisciplinary combination of primary material and secondary scholarship.

➜ View the full title list.

With a focus on the global history of the middle ages, the Medieval World Reference Library provides students and instructors with accessible, expert reference works covering a rich breadth of subject areas. From Medieval life and culture, and a history of the Vikings, to Medieval literature, and the rise and fall of the Medieval world, this collection is an invaluable go to resource for scholars of the global middle ages. The collection expands beyond the traditional western focus to provide an in depth look at life across the medieval world from a truly global perspective, providing students and scholars with a unique resource to globalise their curriculum and enrich their independent research.

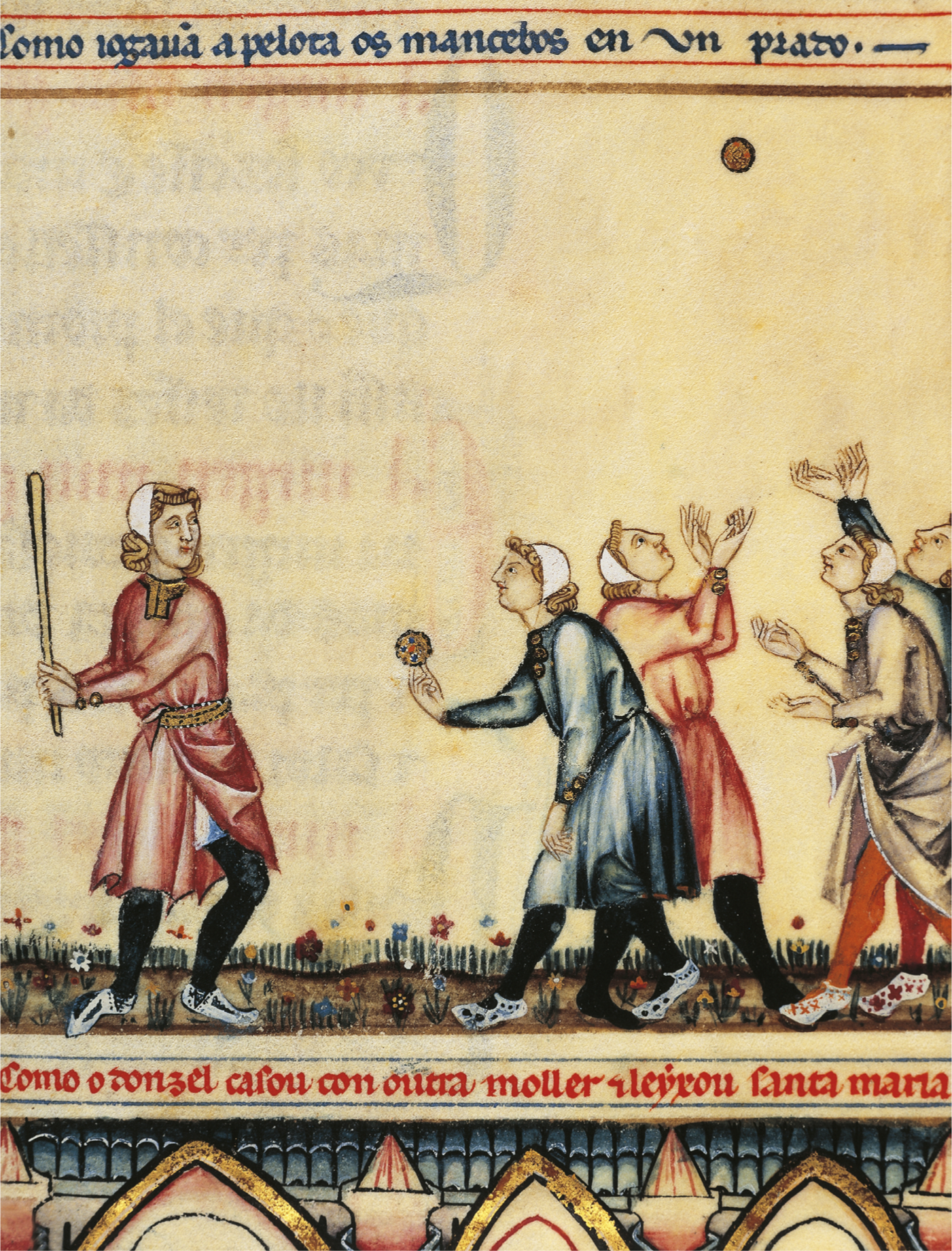

➜ Learn more about the Medieval World Reference Library.From the beginning of time, humans have created sports and games that teach skills, promote leisure, and encourage friendly competition, passing them on through the generations. By studying these histories, we can learn much about the culture and traditions of our ancestors. From gladiatorial combat to knightly tournaments and from hunting to games and gambling, sport and games have been central to human culture. We have brought together a carefully curated collection of eBook chapters, encyclopedia entries, and digitised primary sources from across the Bloomsbury Medieval Studies platform, dedicated to this fascinating area of study.

This Topic in Focus is your guide to step into the global Middle Ages and learn more about the games, tournaments and sports enjoyed by the peoples of the medieval world.

A Cultural History of Sport in the Medieval Age covers the period 600 to 1450. Lacking any viable ancient models, sport evolved into two distinct forms, divided by class. Male and female aristocrats hunted and knights engaged in jousting and tournaments, transforming increasingly outdated modes of warfare into brilliant spectacle. Meanwhile, simpler sports provided recreational distraction from the dangerously unsettled conditions of everyday life. Running, jumping, wrestling, and many ball games - soccer, cricket, baseball, golf, and tennis – had their often violent beginnings in this period. In this chapter, Grant A. Gearhart explores how Athletic competition played an important role in shaping identity in the medieval age.

From the Greenwood Encyclopedia of Global Medieval Life and Culture, discover the board and strategy games that were enjoyed by the peoples of the global middles ages. From the early sixth century c.e., Indians played a parlor game called Chaturanga, a direct ancestor to the modern game of chess which mimicked the ancient Indian battlefield. In Pre-Columbian Mesoamérica, Patolli is the Nahuatl term for a board game that was widely played in central and southern Mesoamérica by such civilizations as the Classic Maya (250–909) and the Aztecs (1325–1521). Played on an X shaped board with tokens and beans, patolli involved a great deal of luck—provided by the god of patolli, Macuilxochitl.

The Middle Ages have provided rich source material for physical and digital games from Dungeons and Dragons to Assassin’s Creed. Playing the Middle Ages addresses the many ways in which different formats and genre of games represent the period. It considers the restrictions placed on these representations by the mechanical and gameplay requirements of the medium and by audience expectations of these products and the period, highlighting innovative attempts to overcome these limitations through game design and play. Click here to read this chapter, which delves into the representations of medieval gender archetypes in modern fantasy role-playing games.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies offers a rich collection of digitised images from the Metroolitan Medieval World, providing access to objects from across the medieval globe. Learn more about this game piece from late-twelfth century Cologne, Germany. A walrus ivory carving, the piece is inspired by the story of Apollonius of Tyre, showcasing the burial of his wife at sea. Or explore this Folio from an illuminated manuscript created in Isfahan, Iran, during the first half of the fourteenth century. Depicting a scene from the Book of Kings (Shahnama), it shows the Persian vizier Buzurgmihr challenging an ambassador to a game of chess.

Since the time of Charlemagne, knights had sometimes staged mock battles for training. When there was no war, young knights had to be toughened up by facing danger and being injured. Tournaments made training into a sport. During the 12th and 13th centuries, the main feature was a large mock battle, the melee. Far more than any other sport, tournaments were violent and caused severe injuries. Knights went into the field as well armored as they were in battle, and although they often used blunt weapons, the violence was still savage. Click here to discover more about medieval tournaments from All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World.

To celebrate the launch of a brand new volume from the Medieval Clothing and Textiles series, we have brought together a carefully curated collection of eBook chapters, encyclopedia entries, and digitised primary sources from across the Bloomsbury Medieval Studies platform, dedicated to this fascinating area of study.

Explore a carefully curated collection of free content with this vibrant Topic in Focus on the theme of Fashion across the medieval world.

Medieval Clothing and Textiles collection provides access to the entire catalogue of Boydell & Brewer's market leading series. The series draws from a range of interdisciplinary scholarship and features multiple examinations of specific clothing items - from wimples and tippets, to hoopskirts, capes and headdresses – as well as studies in the weaving, embroidering, and exporting of clothing and textiles around Medieval Europe. Popular subjects such as masculinity, the history of women, religious clothing, and the representation of clothing and textiles in literature, tapestries and arts are well covered. This rich collection has been updated with a brand new volume exploring topics such as linen armor, bridal goods, medieval silks and depictions of women textile workers.

➜ Click here to explore Volume 18 of the Medieval Clothing and Textiles series.

During the medieval period, people invested heavily in looking good. Drawing on a wealth of pictorial, textual and object sources, A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age examines how dress cultures developed – often to a degree of dazzling sophistication – between the years 800AD to 1450AD. Beautifully illustrated with 100 images, this unique reference work presents an overview of the period with essays on textiles, production and distribution, the body, belief, gender and sexuality, status, ethnicity, visual representations, and literary representations. This particular chapter explores how visual appearance lies at the basis of the expression of cultural identity.

➜ Click here to read more about the link between fashion and ethnicity.

Commissioned by Arc Humanities Press and exclusive to Bloomsbury Medieval Studies, the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages takes an inclusive approach to the history of the middle ages. This pioneering collection provides readers with scholarly articles by global contributors and specialists in all things Medieval, to bring the medieval world alive. The vibrant series includes visual object studies of culturally significant items, such as this Epitrachelion – a Greek stole from the sixteenth century. Read an analysis of this fascinating item from dual perspectives, with this Case Study from the perspective of Iconography, and this Case Study from the perspective of Art History.

➜ Click here to read more articles from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages.

With over 200 color illustrations, Byzantine Silk on the Silk Roads takes us on a journey from the past to the present, too, where Byzantine story-telling and image-making is revisited, through color, imagery and pattern, in contemporary fashion collections. Exploring Byzantine culture through a contemporary filter, the book shows how the Byzantine era still influences textile and fashion designers today in their choices of materials and colors, and their utilization of images and patterns, acting as a unique source of inspiration to designers and creators in the 21st century. This chapter delves into the rich history of Islamic textiles, which were conspicuous symbols of power and wealth.

➜ Click here to discover more about this fascinating topic.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides access to a rich collection of museum objects from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, including a wide range of images showcasing items of fashion and clothing from the across the Medieval Globe. This feathered tabard was made between the fifteenth and sixteenth century in Peru from cotton and feathers, knotted to create a lush surface. Vivid colors such as green, blue, yellow and orange, are used to create four zoomorphic creatures that resemble birds with anthropomorphic faces and lavish headdresses. Discover this exquisitely preserved piece in more detail, or explore one of the many other images from this rich collection.

➜ Click here to learn more about the feathered tabard.

To celebrate this year’s International Medieval Congress taking place at the University of Leeds in the UK, we have brought together some key resources that explore the complex theme of crisis during the Medieval period.

Crises in the Middle Ages took a multitude of forms ¬ political, religious, environmental — and occurred across the globe. The fascinating scholarly resources explored below interrogate both the cause and impact of each crisis, demonstrating the diversity of experience within different Medieval cultures.

This enlightening chapter from The Decline of Iranshahr, examines the series of disasters that ravaged Mesopotamia, post the completing of the great Nahrawan system: civil wars, invasions, floods, and epidemics. The Arab conquest did not usher in an era of growth and prosperity, and Pete Christensen highlights the significance of the natural disasters, previously overlooked in historical narratives. The mortality of the terrifyingly regular plagues impacted on the labour-intensive agricultural system, and the swamps that were a result of the flood of 628, swallowed up the entire al-Tharthur district in Kaskar and expanded further in the years to follow. Preoccupied with fighting the Arabs, the dihqans failed to oversee the dikes and repair the breaches, lacking both the labour and stable administrative framework due to the recurrent outbreaks of plague. These coalescing forces confirmed a prolonged crisis.

➜ Click here to learn more about this fascinating period.

This chapter from Urban Life and Intellectual Crisis in Middle-Period China, 800–1100 CE explores in depth the crisis facing the Song Literati, which led to their eventual withdrawal from the city. As the imperial examinations gained in prestige and scale during the eleventh century, the study of the classical canon intensified, and the moral pattern set by the ancients started to hold sway among the Literati officials. They envisioned that by stimulating the circulation of money, draining floods and containing fires, they would promote the health of the population, and the empire. Whilst the New Laws had classicist threads, they were not categorically successful and thus provoked intellectual crisis. As de Pee aptly surmises: ‘The city resisted the moral order that literati attempted to impose on it, and instead drew them into the relative values of fashion and competitive consumption.’

This enthralling chapter from Memory and Medievalism in George R. R. Martin and Game of Thrones examines Knighthood in Westeros, the fictional world of George R. R. Martin’s Ice and Fire series. Knighthood is presented to exist in flux; Westeros has undergone structural transformation towards centralisation and social diversification, leaving chivalrous codes clouded. A crisis of government challenging chivalric values pervades, since the gravitational centre upon which chivalrous virtues hinge – the lord – is consistently destabilized, leaving knighthood a matter of individual ethics. Brienne of Tarth is presented as a multi-dimensional female form of knighthood, where chivalric habitus is practiced without devotion to a lord, whilst Ser Jaime exemplifies the warrior knight’s struggles whilst residing in a society where warrior values are obsolete. In re-negotiating his knighthood, Ser Jamie is forced to do battle with conflicts of the mind, not of the sword.

➜ Click here to explore knighthood in its myriad of forms.

Over a decade in the making, this chapter from Byzantium and the Crusades details how the Byzantines used their diplomacy, wealth and innovative thinking to dissipate the unrelenting crisis of attack they faced throughout the mid eleventh century. In the 1050s an approach was made to the Fatimid caliph of Egypt for an alliance against the Seljuk Turks, with an inducement of shipments of grain to alleviate a food shortage. Byzantine diplomacy was equally active in the West, with the bid to neutralize the threat from the Normans of southern Italy. The pragmatic Byzantines initially tried to find terms with the Normans themselves. Then in August 1074, with the assistance of Michael Psellos, Michael VII Doukas made a treaty with Norman leader Robert Guiscard. The Byzantines also recruited Western European mercenaries. In the face of attack from all directions, the Byzantines adopted ingenious methods to avert crisis.

➜ Click here to find out more about the Byzantine tactics to alleviate crisis.

The Bloomsbury Medieval Studies is excited to introduce a brand new eBook collection featuring key titles from ABC-Clio’s market leading list, including the pioneering Daily Life series, and much more. This vibrant collection provides access to engaging and accessible eBooks that explore the diverse history of Medieval life and culture, from science and technology in medieval life, and the history of crime and punishment, to religious exchanges, the culture of Medieval games, and more. This Topic in Focus is your guide to explore the collection and delve into the global Medieval world.

Artifacts from the Ancient Silk Road (2022) explores the interconnectivity of the Eurasian continent from 4000 BCE to 1000 CE, focusing on the role played by Central Asia through which passed the major trade routes, the Silk Roads. In this first object-based study to consider all of the peoples involved on the Silk Roads, objects provide the vehicles for explorations of different aspects of life for the various peoples of the Silk Roads. Open up the Medieval world through these fascinating artefacts from the Ancient Silk Road; discover more about the Sakā tribes of Medieval Kazakhstan with this Golden Warrior from the Issyk Kurgan, or explore the culture of dance and performance in through this gilt silver ewer from the Sasanian Empire.

Buildings and Landmarks of Medieval Europe: The Middle Ages Revealed (2016) makes use of significant buildings as "representative structures" to provide insight into specific cultures, historical periods, and key events, as well as the everyday life of the Middle Ages. Through the use of detailed images, diagrams, vivid descriptions, as well as a concise chronology of the evolution of architecture across Medieval Europe, James B. Tschen-Emmons demonstrates how the construction, design, and function of famous structures can inform our understanding of societies of the past, covering social, political, economic, and intellectual perspectives. Click here to read more about the fascinating cultural and social history of the Mosque of Córdoba in Andalusia, and discover what this iconic landmark can teach us today.

Far from the primitive and barbaric practices the Middle Ages may conjure up in our minds, doctors during that time combined knowledge, tradition, innovation, and intuition to create a humane, holistic approach to understanding and treating every known disease. Medieval Medicine: The Art of Healing, from Head to Toe (2013) investigates the extensive capabilities of physicians who relied on practice, observation, and imagination before the supremacy of mechanistic views and technological aids. Luke DeMaitre provides a comprehensive look at diseases as they were described, classified, explained, assessed, and treated by doctors of the age. This fascinating chapter delves into the history of diseases in the Middle Ages, from poison to pestilence.

Largely anonymous in its composition, and apparently lacking the motivation of fame and commerce, music within a well thought-out system of education served a purpose that goes far beyond casual entertainment or personal professional advancement. Nancy van Deusen's The Cultural Context of Medieval Music (2011) addresses the mental landscape surrounding music that was sung and experienced in the Middle Ages. Offering experience through performance, music exemplified the basic principles of the material and possible measurements of the visible and invisible world, making it an ideal medium for working with unseen substances such as concepts, imaginations, and ideas. This chapter takes a closer look at the resources, material and composition of music as a culture of the mind.

Myths of gods, legends of battles, and folktales of magic abound in the heroic narratives of the Middle Ages. Mythology in the Middle Ages: Heroic Tales of Monsters, Magic, and Might (2011) describes how Medieval heroes were developed from a variety of source materials. Discussing the meanings of medieval mythology, legend, and folklore through a wide variety of fantastic episodes, themes, and motifs, Christopher R. Fee guides the reader through key texts from across the Atlantic and Baltic coasts of Europe, the Holy Roman Empire, the Iberian peninsula, North Africa, Byzantium, Russia, and the far reaches of Persia. Click here to discover more and delve into the exciting world of Medieval monsters, magic, and mythology.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies is excited to once again take part in the 2023 International Medieval Congress taking place this July in Leeds, UK, and online. You will be able find us at the Bookfair, and we will also have a host of information available online too. Whether you will be attending in person or virtually, we look forward to seeing you there.

To celebrate the Leeds Medieval Congress, we have brought together a carefully curated collection of eBook chapters, encyclopedia entries, digitised primary sources, and pedagogical teaching and learning tools from across the Bloomsbury Medieval Studies. Explore a carefully curated collection of free content with this Topic in Focus on the theme of Networks and Entanglements.

This chapter from The Global North (2021), edited by Carol Symes, aims to synthesize archaeological evidence pointing to processes of ecological globalization in forested inland Scandinavia during the time period ca. 500 to 1400 CE. The first part of the empirical discussion focuses on ways of reconstructing networks and contacts by analyzing information from burials. It begins with a distinctive burial tradition of the forested inland region which will be analyzed in relation to the communication network of landscapes and routes described in later Viking Age and medieval textual sources. It contends that these burials provide insights into local initiatives of hunting and craftsmanship, as well as to pre-Viking Age exchange networks crossing the inland forests and mountains.

Katalin Prajda’s Network and Migration in Early Renaissance Florence, 1378-1433 (2018) explores the co-development of political, social, economic, and artistic networks of Florentines working in the Kingdom of Hungary during the reign of Sigismund of Luxembourg. In the literature, there has been much research dedicated to simple historical networks and how they affect various public and private spheres. More rare are those historical case studies, which allow us to trace back the impact of a multiple set of relations. In this chapter, Prajda looks both descriptively at patterns of connectivity and causally at the impacts of this complex network on cultural exchanges of various types, among these migration, commerce, diplomacy, and artistic exchange.

Networks comprise persons scattered amidst disparate societies but sharing kinship, beliefs, or material interests and communicating in some way, or exchanging goods. In this chapter from A Cultural History of the Sea in the Medieval Age (2021), Jonathan Shepard traces stages of development in Eurasia’s inland seas, and in the North Atlantic. Thanks to riverways, there was by c. 1000 interconnectedness of things, persons, and sometimes, ideas. As commerce expanded, routes tended to segment into circuits dominated by specialists. Networks of culturally introverted communities undertook long-distance commerce, while agrarian societies formed supply chains without participating in maritime societies. Yet port cities could, literally, harbor new cults and ambitions. Such contrasts are a feature of maritime networks.

Medieval polities, whether they be empires, kingdoms, dukedoms, etc, were typically ruled by families. Thus, one of the most important ways to examine those polities is by studying the families that ruled them. Even in the medieval Roman Empire, typically known as Byzantium, we see this trend, certainly after the rise of the Komneni in the late eleventh century. There we have multiple members of the Komneni family ruling one after another as emperors and co-emperors. This article by Christian Raffensperger from The Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages explores key families that exemplified the importance not just of familial rule but of the social networks that were created by dynastic marriage in the global Middle Ages.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies is excited to once again take part in the 2022 International Medieval Congress taking place this July in Leeds, UK, and online. You will be able find us at the Bookfair, and we will also have a host of information available online too. Whether you will be attending in person or virtually, we look forward to seeing you there.

In anticipation of the Congress, we have brought together a carefully curated collection of eBook chapters, encyclopedia entries, digitised primary sources, and pedagogical teaching and learning tools from across the Bloomsbury Medieval Studies. Whet your appetite for the big event with this Featured Content on the theme of Borders and Migration.

It is often assumed that those outside of academia know very little about the Middle Ages. But the truth is not so simple. Non-specialists learn a great deal from the myriad medievalisms – post-medieval imaginings of the Medieval world – that pervade our everyday culture. From film and television, to computer games and internet memes, the ‘Medieval’ is an active and vibrant part of our culture today. Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides numerous ways with which to explore this fascinating topic: from eBooks to images, this Featured Content is your gateway into the study of medievalism on screen.

The centrality of animals within Medieval culture is abundantly reflected in the surviving source material: animal fables and zoological encyclopedias in the broadest sense are among the most widely distributed texts of the period, and hardly any building or illuminated manuscript survives that does not feature animals in its decoration. Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides numerous ways with which to explore this fascinating topic: from A Cultural History of Animals in the Middle Ages, and eBook chapters exploring fish farming and plague transmission, to exclusive articles from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages and carefully curated images from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, this Featured Content is your gateway into the global study of animals in the Middle Ages.

Animals were an integral part of the human experience during the Middle Ages. Sharing the environment with mammals, birds, fish, and invertebrates, humans lived in close contact with the animal world and interacted with them on a variety of levels. Therefore a clear understanding of the human cultures of the Middle Ages necessitates understanding their relationships with the animal world. In this exclusive article from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages, Todd Preston explores this complex relationship and the impact animals had on the social, intellectual, and spiritual lives of Medieval people.

Bloomsbury Medieval studies offers a range of pedagogical learning and research tools to support students conducting independent study, as well as tutors creating their own academic programme. In this exclusive Lesson Plan, Sophie Page examines the impact of animals on Medieval religion, philosophy and political ideologies, and of activities like husbandry, the creation of environments and the destruction, conservation and importation of species. Organized week-by-week, each section examines a key aspect of Medieval animal studies and offers selective key reading, thought provoking discussion questions and suggested homework tasks.

Animal studies does not always overlap with broader environmental disciplines. Environmentalists are concerned with issues of extinction and how animal movements and extinctions reflect climate change and other global issues, while scholars and activists concerned with animals focus on philosophical issues of rights and agency, as well as how the characteristics of animals define or limit the human (or not). Both approaches are valid, indeed necessary. This chapter from Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes focuses on how depictions of animals and humans interact in Medieval texts, and attempts to locate those interactions within these broader environmental questions.

A Cultural History of Animals in the Medieval Age, investigates the changing roles of animals in Medieval culture, economy and society in the period 1000 to 1400. The illustrated volume outlines the position of animals in contemporary symbolism, hunting, domestication, sports and entertainment, science, philosophy, and art. This chapter by Lisa J. Kiser looks at the role of animals within Medieval sport, entertainment and menageries. Kiser maintains a strong focus on the Medieval animal participants themselves, for, as Robert Delort observed in 1984, animals have histories, too, and those histories have only begun to be recorded.

In this chapter from Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World, Nükhet Varlik examines the Ottoman plague experience, and the role of animals in plague transmission. Historical scholarship on plague has very recently moved beyond an exclusive reliance on models of rodent-host-vector-to-human transmission. A comparable change can be observed in Ottomanist historiography which explores plague’s connections to flooding, rodent behaviour, and other climatic conditions. While it is imperative to recognize the role of human agency in the spread of plague, it is equally important to broaden the study to the larger environment.

In Fish Trade in Medieval North Atlantic Societies, Val Dufeu reconstructs settlement patterns of fishing communities in Viking Age Iceland and proposes socio-economic and environmental models relevant to any study of the Vikings or the North Atlantic. She integrates written sources, geoarchaeological data, and zooarchaeological data to examine how fishing propelled political change in the North Atlantic.In this chapter Defeu outlines archaeological case studies for reconstructing commercial fishing in the Westfjords and the Mývatn areas of Iceland.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides access to a carefully curated image collection sourced from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, to complement academic research and encourage a well-rounded understanding of Medieval history. Click here to explore 北魏/北齊 彩繪陶鎮墓獸, a Tomb Guardian from the Northern Wei (386–534)–Northern Qi (550–577) dynasty. Made in the mid-to-late sixth century from earthenware with pigment, this tomb guardian was one of a pair and would have been placed at the entrance of a coffin chamber as a guardian of the deceased’s tomb.

Marie de France is among the most prominent authors of Old French texts and a rare female author from the Middle Ages. Her twelfth-century Lais are a series of short narrative poems of romance and adventure. Bisclavret is the tale of a warewolf, a lycanthrope who must take on animal form. Marie explains that “bisclavret” is the Breton term for what is, in Old French, “garulf,” that is, “man-wolf.”Click here to read the Lais of Bisclavret in translation from the original Old French, which is accompanied by Discussion Questions and Further Reading to support further independent study.

Created by opaque watercolour on paper, this digitised ‘Hare’ folio was part of the zoological treatise “Mantiq al-wahsh” (Speech of the Wild Animal) written by Ka'b al-Ahbar. “Mantiq al-wahsh” is an eleventh or twelfth century illustrated manuscript found in Fustat, Egypt. On the verso is a lion, while a hare is depicted on the recto. The verses above the animals contain the title of the text, the author's name, and also identifies the animals below it. Sourced from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, explore this folio in exquisite detail.

Appreciating the fullness and complexity of disability in the Middle Ages means confronting long-lived contemporary assumptions that people who lived with disabilities during this time were markers of sin. Close attention to religious, literary, artistic, and medical evidence helps to create a nuanced and thick cultural history of disability and showcases the agency of—and varied lives led by—people who we might now consider disabled. Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides numerous ways with which to explore the fascinating topic of Medieval disability studies: from A Cultural History of Disability in the Middle Ages, and book chapters that explore the intersection of religion and disability, to exclusive articles from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages and carefully curated research and teaching resources, this Featured Content is your gateway into the study of disability in the Medieval world.

A Cultural History of Disability in the Middle Ages is an essential resource for researchers, scholars and students of history, literature, culture and education. With chapters written by leading scholars in the field of disability studies, it explores topics such as atypical bodies, mobility impairment, chronic pain and illness, blindness, deafness, speech, learning difficulties, and mental health. In this chapter Richard H. Godden looks in depth at the study of mobility impairment: most sources represent the physically impaired using some sort of aid to help them navigate their environment, and such objects are arguably the chief visual signifier of disability in the Middle Ages.

Medieval European understandings and representations of deafness draw heavily on biblical imagery and Galenic medicine, and therefore display a great deal of continuity with ancient traditions. But Medieval writers also use deafness to think through a number of larger cultural debates particular to their period: theological discussions of knowledge, sin, and salvation; philosophical questions about the authenticity and legibility of signs; the iconographic problem of the representation of the invisible. In this chapter, Julie Singer demonstrates how the lived experiences and cultural representations of deaf people in Medieval Europe were far richer and more varied than stereotypes suggest.

Disability theory has strong but complex and troubled links with gender and sexuality studies and specifically with queer theory. The seemingly outward evidence of sexual transgression provided by a physical disability was seen as evidence not just of behavioural history but also of more general tendencies and predispositions. This was met with a mixture of condemnation and erotic fascination. The idea that ‘the lame man does it best’, for example, occurs in Erasmus’s writings as ‘Claudus optime virum agit’ or ‘the lame man makes the best lecher Click here to find out more.

In the Middle Ages, experiences of disability and religious belief intersected in different ways. A seemingly common belief across a variety of cultures, including Medieval Hinduism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam was that physical impairments, in particular, were markers of immoral or sinful behaviour either of the self or of one’s ancestors. In this article from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages, exclusive to the Bloomsbury Medieval Studies platform, Donna Trembinski examines this relationship between religion and impairment in Medieval cultures, and outlines the key debates in this fascinating field of study.

Historical records of canonization processes and miracle collections are a treasure trove for historians studying everyday life. For medieval people, the miracles performed by Christ provided the models for subsequent miracles, which continued to be performed after his life on earth by the saints. Miracles provide a unique source type for the study of medieval illness and health, as well as dis/ability. Click here to read a chapter from Church and Belief in the Middle Ages and find out more.

The perception of los Milagros (miracles) in the Middle Ages was informed primarily by the writings of St. Augustine of Hippo. According to Augustine, miracles ‘were wonderful acts of God shown as events in this world, not in opposition to nature but as a drawing out of the hidden workings of God within a nature that was all potentially miraculous’. For Medieval authors miracles formed part of the supernatural, as did magic, but they were also signs from God, indications of His omnipresence and omniscience. Click here to discover more about los Milagros in Medieval texts..

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies offers a range of pedagogical learning resources to aid individual research and course building. This extensive bibliography by Wendy J. Turner details key books, chapters, articles, essays, surveys, studies and talks on the topic of disability in the Middle Ages, enabling users to orient themselves quickly to facilitate research. The contents are selectively and lightly annotated to provide guidance to accessing the titles and/or to indicate their value or limitations as resources, and links and URLs are provided for online resources to enable a seamless access to material.

As the field of disability studies has grown over the last 40 years, there has been increasing critical interest in how current notions and attitudes toward the impaired were shaped historically. An examination of the disabled as they appear in Medieval texts is a useful tool to discover what ideas about physical difference might have meant to the society at large. This chapter from Viewing Disability in Medieval Spanish Texts introduces a heretofore largely unexplored body of work within disability studies, and shows that in texts produced in Medieval Spain the disabled frequently appear as historical figures, members of a legal category, and as fictive characters.

Bloomsbury Medieval studies offers a range of carefully curated Subject Guides that introduce students to key subject areas, support instructors in their teaching and serve as jumping-off points for further research. Click here to download the Subject Guide PDF on Illness and Injury which brings together the key eBook, article, image, reference and pedagogical material from across the Bloomsbury Medieval Studies platform. This extensive Subject Guide provides users with a simple shortcut to help them find the material they need, with links that can easily be added to a course syllabus or reading list.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies is happy to introduce a new and exclusive series of Commentary Articles, designed to provide expert introductions and analyses of primary sources. In this article Dr Rosamund Oates sheds light on the historical context, reception and significance of the Liber Chronicarum, also known as the Nuremberg Chronicles. Click here to explore the digitised Liber Chronicarum incunabula (1493) from Senate House Library and discover each page in exquisite detail.

This exclusive article from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages takes a closer look at S. Lorenzo de El Escorial, Bibliotheca del Real Monasterio, R I 19, one of only two extant Byzantine manuscripts that include examples of the Akathistos hymn in Greek. The unusual and innovative compositions of this invaluable manuscript, such as the headpiece miniatures preceding each stanza, capture the reader’s attention and stimulate further contemplation of the hymn’s content, beyond what is presented in the text.

Though it is easy to forget, manuscripts existed for over a thousand years before Europe’s first printing press created the 1455 Gutenberg Bible. In Books Before Print, Professor Erik Kwakkel provides an in-depth introduction to the fascinating history of these medieval texts and examines “what is arguably the most notable feature of manuscripts: their individuality”. This intricately illustrated book highlights extraordinary continuities between medieval book culture and modern-world communication through in-depth analysis of medieval pop-up books, posters, speech bubbles, book advertisements, and even sticky notes.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies offers carefully chosen images of medieval manuscripts sourced from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, to complement academic research and encourage a well-rounded understanding of medieval history. Click here to explore Night-Shining White, a mid-eight century handscroll made during the Tang dynasty in China. Created by Han Gan, the handscroll features red seals and many inscriptions. One such inscription explains how Han Gan came to depict a vivid image of Night-Shining White, a horse owned by Emperor Xuanzongthe.

Arguably one of the most popular late medieval Icelandic romances, the Nítíða saga survives in sixty-five manuscripts ranging from the Middle Ages to the beginning of the twentieth century. It is very likely that the saga once also appeared in many more manuscripts, which are now fragmentary or simply lost altogether. Each time the story was written down, it took on a new form. This chapter from Popular Romance in Iceland explores the textual variation in Nítíða saga’s manuscript tradition, and what these manuscripts can reveal about the Icelandic people who created and read them at different points throughout history.

The folio of Green Tara was part of an Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita manuscript, a twelfth century text of the Pala period, thought to have originated in Bengal, India or Bangladesh. In the middle of the folio sits the figure of Tara, who is seated on a lotus pedestal underneath a polylobed arch. Beside her are two female figures, one holding a vijra while the other, Mahakali, is holding skullcup and knife. Click here to discover the folio from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and explore each page in detail.

While ‘the physical’ and ‘the digital’ are often set in opposition, they share the same belief that these objects’ physical forms—their words, miniatures, margins, fore-edges and bindings—are vitally important to uncovering complex textual meanings, and to recovering the identities, concerns, and desires of the people who made and read these books centuries before us. With this in mind, Bridget Whearty seeks to promote a codicology of the digital medieval book which fosters a richer and more rigorous curiosity into the digital labour that makes and maintains digital medieval books.

In the recently published Medieval Literature on Display, Alexandra Sterling-Hellenbrand uses collections from two German museums as case studies for a vibrant, imaginative, and provocative enactment of 21st-century medievalism. Click here to join Sterling-Hellenbrand on a virtual tour of the Museum Wolfram von Eschenbach and find out how, in reconstructing and transforming medieval narratives for a contemporary audience, the museum enacts the process of medievalism and reveals how memory, through the lens of the Middle Ages, shapes modern cultural identity and heritage.

Each manuscript has a story to tell about its afterlife. As a class of artefact, manuscripts have often been subject to huge changes in the ways in which they have been received, used, understood and valued. Some manuscripts are associated with particularly long and eventful afterlives, being the subject of legends of preservation, curation, longevity and transfer of ownership that are still unfolding. The conservation of manuscripts is key to supporting research into the history of medieval texts. Click here to learn more about the historical development of manuscript heritage, and its potential for the future.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides numerous ways with which to explore the fascinating topic of magic from a global perspective: from primary texts of witch trial proceedings and a scanned witch-hunting handbook, to articles and book chapters that examine the political and social context of magic, sorcery and demon beliefs around the world.

The most famous of the witchcraft manuals, the Malleus Maleficarum – or Hammer of Witches – of 1486 revised key perceptions about the practice of magic and contributed to the burgeoning era of witch trials at the close of the Middle Ages. Its impact was in part due to its emphasis on the figure of the female, domestic witch over the previous association of sorcery with the male, learned necromancer. Access a high-resolution, zoomable version of the original text here.

A woman with great influence in the state affairs and finance of the Mongol Empire through her friendship with Törägänä Khatun, Fatima Khatun’s downfall in 1245 was wrought by accusations of sorcery from the amirs and noyans of the ulus. As described in Wheeler M Thackston’s commentary on the Persian Histories of the Mongol Dynasties, the grandson of Genghis Khan and third Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, Güyük Khan, sentenced her to death for supposedly causing his brother’s illness through magic.

This folio from a fourteenth century manuscript, most likely originating from Isfahan, Iran, shows a scene from the Book of Kings (Shahnama). The hero Isfandiyar plays a string instrument and uses his music and the promise of wine to lure a sorceress closer so that he may strike her with his sword.

“Some say that the genies [jinn] spoke to her, others that she was a sorceress and a fortune teller” - one of the most demonstrably powerful women in the eleventh-century Maghreb, Zaynab bint Ishaq al-Nafzawwiyya had a crucial role in the rise of the Almoravid Empire and in the complicated politics of its court. Read more about Zaynab’s political goals and reversals of fortune on her way to queenship in this eBook chapter.

The founder of the Zhou Dynasty and one of the most controversial sovereign rulers in Chinese imperial history, Wu Zetian was known for surrounding herself with magicians. She used both magical and religious symbolism to legitimize her swift rise to the dragon throne, where she remained from 690 to 705. Read more about Wu Zetian’s rise to power and the auspicious omens and superstition-based performances that she used to bolster her position in this study of global queenship.

Accusations of political crimes and treason involving magic abounded in this bloody conflict between the Yorkists and Lancastrians of England at the close of the Medieval period. In one such instance during the reign of Edward IV in 1477, Thomas Burdett was accused of engaging John Stacy and Thomas Blake to calculate ‘by art magic, necromancy and astronomy, the death and final destruction of the king and prince’. Learn more about the fate of the accused and magic as a political crime in Medieval England.

“Moreover, the accused gave his daughter Françoise, then aged six months, to this devil, his teacher, and Beelzebub, his teacher, killed her; and thereafter…committed and perpetrated many acts of sorcery by following his teacher’s instructions on what he should do and when he should do it.” In a series of readings from trials of witches and other workers of magic conducted by inquisitors 1245-1540, many of the accused stand trial for the summoning of demons.

A new article from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages explores the medieval understanding of the causes of mental illness, now generally accepted to be more varied and nuanced than often thought. Contemporary Western texts suggest a range of causes were appreciated-namely grief, illness, alcohol, poor diet, or an imbalance in the humours. However, religious belief in demons as a cause of mental illness were also prevalent: both the French theologian Thomas Aquinas and the Silesian scholar Witelo believed that demons could enter the body and upset the balance of the humours.

The early fathers of the church in Europe attempted to forge a new Christian orthodoxy out of existing beliefs and had to redefine the practice of magic in a Christian context. This meant insisting that all magic was demonic in origin, and that the practice of it was always morally wrong. Learn more about the uneasy relationship between Christianity, proto-scientific epistemology and the concept of demons in this eBook chapter.

Bloomsbury Medieval Studies provides numerous ways with which to explore the fascinating topic of queenship from a global perspective: from articles and book chapters that place this concept in its historical and cultural contexts, to case studies of specific powerful women of the period and depictions of queens in works of art.

The study of queenship brings together the biographical study of the lives of royal women with an analysis of their agency and activity. Queenship scholars draw on a number of different disciplines including history, literature studies, art history, politics, gender studies, archaeology, and religious studies in order to thoroughly scrutinize the wide variety of evidence from the lives of royal women.

Read a thematic overview of Global Queenship from the Encyclopedia of the Global Middle Ages.

Tamar the Great (born ca. 1160, r. 1184–1213) ruled the medieval kingdom of Georgia at the height of its political power and cultural influence. Tamar has been neglected in historical works outside of Georgia, particularly in western languages, but scholars have recently begun to investigate her reign, examine her alongside other monarchs and speculate about the factors that enabled her success.

Before Wu Zetian’s reign (690–705) no woman had ever dared to present herself as emperor. She was the first, and last, woman who not only played a patriarchal role, but who convinced her vassals that she deserved the “Mandate of Heaven” (tianming 天命).

Eleanor of Aquitaine (d. 1204) was one of the most powerful queens in medieval Europe as well as a noteworthy patron of the arts. Her spectacular life was marked with momentous events and renown, through which she navigated the complex terrain of going on crusade, dealing with divorce and remarriage, negotiating conflict with her second husband that would result in her imprisonment, and correspondence with key contemporary figures such as Bernard of Clairvaux and Abbot Suger.

The most notable amongst all of the royal women of the Sultanate of Delhi was the regnant queen Razia (1236–1240), who adopted the gender-neutral title of Sultan. Razia has a unique position in the history of India, as both the only regnant queen of Medieval India and woman to sit on the throne of Delhi.

Queen Kunigunde, wife of Holy Roman Emperor Henry II, is depicted in stained glass with a halo, crown and holding a sceptre. She is reported to have been politically active, taking part in Imperial councils and advising her husband. She was eventually canonized as Saint Kunigunde by Pope Innocent III in March 1200.